Prospect Hill Flag Debate

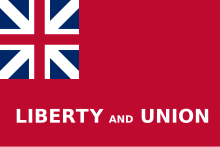

According to tradition, the first unofficial flag of the United States, the Grand Union Flag ("Continental Colors"), was raised by George Washington at Prospect Hill in Somerville, Massachusetts on 1 January 1776, in an attempt to raise the morale of the men of the Continental Army. There was a 76-foot liberty pole situated on Prospect Hill on 22 August 1775 that "was visible from most parts of the American lines, as well as from Boston".[1][note 1] The standard account has been questioned by modern researchers, most notably Peter Ansoff, who in 2006 published a paper entitled "The Flag on Prospect Hill" where he advances the argument that Washington flew the British Union Flag and not the Continental Colors that bears 13 stripes.[3] Others, such as Byron DeLear, have argued in favour of the traditional version of events.[4][5][6]

Background[edit]

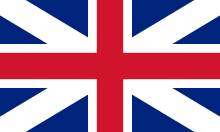

The Union Flag featuring the crosses of Saint George and Saint Andrew was introduced in 1606 to symbolise the dual status of King James I as ruler of England and Scotland. It was flown at sea as a maritime flag and from forts and royal castles. It formed the basis of the "King's colours" bestowed on army regiments. In 1801, the red cross of Saint Patrick was added to herald Ireland's entry into the United Kingdom. Beginning in the 19th century, it achieved customary use as the national flag of the UK when it was "inscribed with slogans as a protest flag of the Chartist movement".[7][8]

The colonists still associated the King's symbols with their cause even after hostilities between the UK and the Thirteen American colonies erupted in April 1775 with the battles of Lexington and Concord. Colonial propaganda generally made the distinction between the Crown, to which most colonists still remained loyal, and the parliament and the parliamentary executive, which was viewed as the cause of their grievances.[9] This sentiment finds expression in a verse affixed to the flag pole in Taunton, Massachusetts that mentions:

... Zeal for the Preservation of Their Rights as Men and American Englishmen ... Resentment of The Wrongs and Injuries offered to the English colonies in general, and This Province in particular ... Through unjust Claims of A British Parliament and the Machiaveilan Policy of a British Ministry ... [9]

The reference to "the English colonies in General" points to the way the Union Flag was seen as a protest symbol in that "its very name hinted at the idea of a union among the colonies" being "a concept that was not viewed favorably in London".[10] The use of the Union Flag was "in a sense a challenge to authority" as the concept of a national flag that represents both the government and the people is modern and did not prevail in the 18th century.[10]

In a speech given on 27 October 1775 at the opening of parliament, copies of which reached Boston by the end of December 1775, the King George III "made it clear that he had no sympathy for the distinctions made by the colonists"[11] stating:

... [the colonies] now openly avow their revolt, hostility, and rebellion. They have raised troops, are collecting a naval force; they have seized public revenue, and assumed to themselves legislative, executive, and judicial powers. .. The authors and promoters of this deliberate conspiracy ... meant only to amuse by vague expressions of attachment to the Parent State, and the strongest protestations of loyalty to me, whilst they were preparing for a general revolt.[11]

It is not known for certain when the Continental Colours was designed or by whom. It was raised for the first recorded time aboard the USS Alfred on 3 December 1775 by Senior Lieutenant John Paul Jones. Construction of the specimen flown from the Alfred has been credited to Margaret Manny.[12]

Arguments for the British Union Flag[edit]

All three known eyewitness accounts of the flag raising on Prospect Hill state that it was the "Union Flag". Ansoff posits that the terms "Grand Union" and "Great Union" were not in use during the American Revolution "but were retrospectively applied to the stripe union flag by 19th century historians".[13]

Primary souces[edit]

George Washington's letter to his friend Joseph Reed, dated 4 January 1776, states that:

...we had hoisted the Union Flag in compliment to the United Colonies; but behold! it was received in Boston as a token of the deep impression the Speech had made upon us, and as a signal of submission, so we learn by a person out of Boston last night. By the time, I presume, they begin to think it strange that we have not made a formal surrender of our lines. [...][14]

There appears to be no reason arising from Washington's words or the context to doubt that he was referring to anything other than the British Union Flag and that what he was conveying to Reed "was the irony of the Army's hoisting a symbol of the Crown just before receiving the King's message of hostility toward the colonies".[14] The Continental Colors was devised in Philadelphia for use by the nascent Continental Navy. At the time of the flag raising on Prospect Hill, it had never been formally adopted, and Washington may not have even been aware of the existence of the Continental Colors by then, which is not mentioned in any of his voluminous correspondence with the Continental Congress in the period July to December 1775.[14]

The second account comes from an anonymous captain of a British merchant ship that arrived in Boston on 1 January 1776. In a lengthy letter to the ship owners dated 17 January 1776, he states:

I can see the Rebels' camp very plain, whose colours, a little while ago, were entirely red; but, on the receipt of the King's speech, (which they burnt,) they have hoisted the Union Flag, which is here supposed to intimate the union of the Provinces. [15]

Ansoff notes that his correspondents in London would have no knowledge of the Continental Colors and that if the flag raised on Prospect Hill differed from the British Union Flag, "it seems likely the captain would have further described it".[16] The anonymous author makes the same assumption Washington believed the British had made being "that raising the King's colours was a reaction to the King's speech".[16] However, whereas Washington had suggested to Reed in jest that it was interpreted as a sign of submission, the captain saw it as signalling colonial unity instead.[16]

There is a third eyewitness account contained in a letter by British Lieutenant William Carter of the 40th Regiment of Foot dated 26 January 1776, which states:

The King's speech was sent by a flag [of truce] to them on the 1st instant. In a short time after they received it, they hoisted a union flag (above the continental with the thirteen stripes) at Mount Pisga;[note 2] their citadel fired thirteen guns, and gave the like number of cheers.[16]

Unlike the other eyewitness accounts, Carter refers to "thirteen stripes" although he does not specify whether they are horizontal or vertical. According to Ansoff, "it seems fairly clear from his phrasing that he is talking about a Union Flag flying above another, striped flag". He speculates that if there was a flag hoisted beneath the Union Flag, it may have been "one of the signal flags that were commonly flown on Prospect Hill". Amid the salutes and cheers, Carter may have assumed it was designed to represent the colonies. Washington may have "failed to mention it as it was not pertinent to the point he was making to Reed". Ansoff concedes that Carter may have been "giving a muddled description of a single flag with both the union crosses and thirteen stripes". However, if so, he considers it "extremely unlikely" that Washington and the anonymous ship captain would have referred to it as the Union Flag without any further qualification.[16]

Secondary sources[edit]

There are two secondary accounts that are frequently cited in the vexillological literature. The first appeared on 15 January 1776 in Philadelphia's Dunlap's Pennsylvania Packet or the General Advertiser which states:

Our advices conclude with the following anecdote:-That upon the King's Speech arriving in Boston, a great number of them were reprinted and sent out to our lines on the 2nd of January, which being also the day of forming the new army, the great Union Flag was hoisted on Prospect Hill, in compliment to the United Colonies.-this happening soon after the Speeches were delivered at Roxbury, but before they were received at Cambridge, the Boston gentry supposed it to be a token of the deep impression the Speech had made, and a signal of submission-That they were much disappointed at finding several days elapse without some formal measure leading to a surrender, with which they had begun to flatter themselves.[17]

Ansoff thinks it "very likely" the author has Washington's letter to Reed available to them given the similarity in phrasing. It appears that it was not uncommon for private correspondence to form the basis of newspaper articles and Washington complained about this in a previous letter to Reed. Ansoff believes that this account is the source of the term "Great Union" that historians subsequently used as the name for the striped Continental Colors.[18]

There was another secondary account that appeared in the 1776 edition of the British publication The Annual Register that states:

The arrival of a copy of the King's speech, with an account of the fate of the petition from the continental congress, is said to have excited the greatest degree of rage and indignation amongst them; as a proof of which, the former was publicly burnt in the camp; and they are said upon this occasion to have changed their colours, from a plain ground, which they had hitherto used, to a flag with thirteen stripes, as a symbol of the number and union of the colonies".[18]

Although this account refers to a "flag with thirteen stripes", Ansoff points out that "it is not an original account". It was not published until 25 September 1777 which was "long after the striped Continental Flag had become known to the British" and by which time it "had been superseded by the stars and stripes". The plain ground changing to a field of thirteen stripes faithfully "recalls the transition from the British red ensign to the American Continental colors". Absent is any reference to the Union Flag and Ansoff concludes that the editors "probably conflated this with accounts of the event at Prospect Hill".[18]

Origin of the terms "Great Union" and "Grand Union"[edit]

Ansoff asserts the idea that the Continental Colors was raised on Prospect Hill had originated in a footnote in a history of the siege of Boston published by Richard Frothingham in 1849. The relevant extract which relies on several previous primary sources states that:

Another flag alluded to in 1775 [sic], called "The Union Flag" … Washington (Jan. 4) states … that it was raised in compliment to the United Colonies. Also, that without knowing or intending it, it gave great joy to the enemy, as it was regarded as a response to the king's speech. The Annual Register (1776) says the Americans, so great was their rage and indignation, burnt the speech, and "charged their colors from a plain red ground, which they had hitherto used, to a flag with thirteen stripes, as a symbol of the number and union of the colonies". Lieut. Carter, however, is still a better authority for the device on the union flag. He was on Charlestown Heights, and says, January 26: "The king's speech was sent by a flag to them on the 1st instant. In a short time after they received it, they hoisted a union flag (above a continental with thirteen stripes) at Mount Pisgah; their citadel fired thirteen guns, and gave the like number of cheers." This union flag also was hoisted at Philadelphia in February, when the American fleet sailed under Admiral Hopkins.[note 3] A letter says that it sailed 'amidst the acclamations of thousands assembled on the joyful occasion, under the display of a union flag, with thirteen stripes in the field, emblematical of the thirteen united colonies".[20]

Schuyler Hamilton reinforces the idea that a singular flag was flown on Prospect Hill in his 1853 history of the American flag. Quoting Carter's letter Hamilton remarks:

... we may expect inaccuracies in the description of a flag newly presented to [British observers], and which, even to an offer on Charlestown Heights, who, appears, was at some pains to describe it, appeared to be two flags … [19]

Hamilton also refers Philadelphia newspaper account dated 15 January 1776 that used the term "Great Union Flag" stating:

We observe [that] … in the extract from the newspaper account of this, that the flag was displayed on Prospect Hill, and that it must have been a peculiarly marked Union flag, to be called the Great Union Flag. As this was the name given to the national banner of Great Britain, this indicates this flag as the national banner of the United Colonies … they were British colonies: and, as we have shown, they used the British Union but now, they were to distinguish their flag by its color would naturally be suggested as being striking, as enabling them to show the number and union of the colonies … Hence, probably the name The Great Union Flag, given to it by the writer in the Philadelphia Gazette, before quoted … indicated, as respecting the Colonies, precisely what the Great Union Flag of Great Britain indicated respecting the mother country.[21]

Ansoff notes that it is "somewhat misleading" for Hamilton to say that "Great Union Flag" was the "name given to the national banner of Great Britain". The term "great union" is found in a 1768 royal warrant concerning the colours carried by British infantry regiments and applies "generically to the design of the combined English and Scottish crosses, rather than to a particular flag". The reference in the newspaper report to the "great union" flag is probably a description rather than the name of the flag and "supports the idea that it was a union flag with the combined English and Scottish crosses overall".[22] Hamilton's statement that the flag raised on Prospect Hill "must have been a peculiarly marked Union flag, to be called the Great Union Flag" is unsubstantiated yet his "use of the term as a proper name has been perpetuated by later historians, and is often used to refer to the Continental Colors".[23]

The first reference to the Continental Colors as the "Grand Union" is George Preble's 1872 history of the American flag, which states:

A letter from Boston, in the 'Pennsylvania Gazette,' says "The grand union was raised on the 2d, in compliment to the United Colonies.

Preble evidently substitutes the word "grand" for "great" which appeared in the letter published in the Pennsylvania Gazette on 17 January 1776 and given his work is accepted as the seminal history of the American flag "his mistake has been perpetrated in vexillological and general literature ever since".[23]

Arguments for the Continental Colors[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2024) |

Byron DeLear has argued in favour of the conventional history based on a review of "eighteenth-century linguistic standards, contextual historical trends, and additional primary and secondary sources".[24]

Primary sources[edit]

In his 2014 paper "Revisiting the Flag at Prospect Hill: Grand Union or Just British", Delear lists a number of additional primary sources where the Continental Colours are contemporaneously referred to using the descriptor "union".

Dated between December 1775 and March 1776[25] they are:

- "Union Flag" (Account book of Philadelphia ship chandler, James Wharton, 12 December 1775)[2]

- "UNION FLAG of the American States" (The Virginia Gazette, 17 May 1776)[26]

- "Union flag, and striped red and white in the field" (Letter to Delegates to Congress from Richard Henry Lee, 5 January 1776)[27][note 4]

- "Continental Union Flag" (Resolution of the Convention of Virginia, 11 May 1776, published in the Virginia Gazette, 18 May 1776 edition)[28]

- "1 Union Flag 13 Stripes Broad Buntg and 33 feet fly" (Bill for purchase of Continental Colours as itemised in James Wharton's day book, 8 February 1776)[27]

- "union flag with thirteen stripes in the field emblematical of the thirteen United Colonies" (Account of sailing of the first American fleet, Newborn [sic], 9 February 1776)[27]

- "a Continental Union Flag" (The Virginia Gazette, 20 April 1776)[27]

- "striped under the union with thirteen strokes" (Taken from several publications in different forms between March and July 1776)[27]

See also[edit]

- Eureka Jack Mystery, debate over flag arrangements at the Eureka Stockade

- Prospect Hill Monument

Notes[edit]

- ^ To begin with the flag pole on Prospect Hill was a mast taken from the British schooner HMS Diana following the Battle of Chelsea Creek on 27-28 May 1775.[2]

- ^ Prospect Hill was derisively dubbed "Mount Pisgah" by the British as it commanded a view of their defensive lines on the Charlestown Peninsula. As with Moses who ascended the summit so referred to in the Bible, the Americans could also see the inaccessible "promised land" of Charlestown.[1]

- ^ In fact the Continental fleet under the command of Hopkins actually departed from Philadelphia in January 1776.[19]

- ^ DeLear states that "as Ansoff mentions, there is evidence to suggest that this letter was written in December 1775, perhaps as early as 2 December, the day before the Grand Union's unveiling".[26]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Ansoff 2006, p. 81.

- ^ a b DeLear 2014, p. 61.

- ^ Ansoff 2006.

- ^ DeLear 2014.

- ^ DeLear 2018.

- ^ Orchard, Chris (30 December 2013). "Research upholds traditional Prospect Hill flag story". Patch. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ Ansoff 2006, p. 78.

- ^ Smith 1975, p. 188.

- ^ a b Ansoff 2006, p. 79.

- ^ a b Ansoff 2006, pp. 79–80.

- ^ a b Ansoff 2006, p. 83.

- ^ DeLear 2014, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Ansoff 2006, p. 77.

- ^ a b c Ansoff 2006, p. 84.

- ^ Ansoff 2006, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b c d e Ansoff 2006, p. 85.

- ^ Ansoff 2006, pp. 86–87.

- ^ a b c Ansoff 2006, p. 87.

- ^ a b Ansoff 2006, p. 89.

- ^ Ansoff 2006, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Ansoff 2006, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Ansoff 2006, p. 90.

- ^ a b Ansoff 2006, p. 91.

- ^ DeLear 2014, p. 19.

- ^ DeLear 2014, p. 35.

- ^ a b DeLear 2014, p. 62.

- ^ a b c d e DeLear 2014, p. 63.

- ^ DeLear 2014, pp. 62–63.

Bibliography[edit]

Books[edit]

- DeLear, Byron (2018). The First American Flag: Revisiting the Grand Union at Prospect Hill. Talbot Publishers. ISBN 978-1946831026.

- Smith, Whitney (1975). Flags Through the Ages and Across the World. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-059093-9.

Journals[edit]

- Ansoff, Peter (2006). "The Flag on Prospect Hill". Raven: A Journal of Vexillology. 13: 77–100. doi:10.5840/raven2006134. ISSN 1071-0043.

- DeLear, Byron (2014). "Revisiting the Flag at Prospect Hill: Grand Union or Just British?" (PDF). Raven: A Journal of Vexillology. 21: 19–70. doi:10.5840/raven2014213.

Newspaper reports[edit]

- Orchard, Chris (30 December 2013). "Research upholds traditional Prospect Hill flag story". Patch Media. New York. Retrieved 26 May 2024.